This is the first in a series of blog posts about “how we design” at the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

At the time of writing (September 2019) we are moving from a broad discovery phase of work to an ‘Alpha’ phase for our primary service which enables people to “Get funding for a heritage project”.

This is the time we try out different solutions to the problems we learnt about during discovery.

This where prototypes come in, they help us to learn by doing.

What is a prototype?

A prototype is an experimental version of a product or service that allows us to explore our ideas.

Prototypes can be anything, so long as they do a good enough job of representing the thing we intend to test.

Why do we use prototypes?

They help us to learn what the right solution is (or is not!)

We create prototypes to help us learn about a problem we want to solve and potential solutions to it.

They turn our ideas into testable things we can use to show the intention of a design concept to our users.

We do this with user research to gain insights by watching what people do and listening to what they tell us when using the prototype.

They save time, energy and money

The quicker and easier they are to produce and change, the better. Prototypes should be something design teams are happy to throw away.

The sooner you learn something isn’t working the better. It saves time and effort which costs money.

Often teams using prototypes make progress quicker when the opposite feels like it would be true. The speed does not come by working flat-out with no breaks though.

The speed of progress comes from it taking much less effort to go down dead-ends in a prototype, which means we can do more in the same amount of time which ultimately gets us closer to our destination faster. Decision makers have more assurance that the team is delivering the right thing and sooner.

If you have invested time, energy and money into creating something you are less likely to accept that it is not working.

Testing ideas cheaply and quickly with prototypes gives us the space to get it wrong when it is easy to correct, so that we get it right when it counts. That also means it’s more reassuring for the people in charge of budgets.

I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work. — Thomas A. Edison

The types of prototype

Low fidelity prototypes

Low fidelity (often referred to as Lo-fi) prototypes are simple and low-tech concepts.

We use them so we can spend more energy on our ideas rather than technical details.

Low fidelity prototypes lower the barrier to participation which is important. It means people who do not see themselves as designers can take part in the design process.

Everyone can doodle and everyone can learn to use a simple prototyping tool within a couple of hours. Pen and paper or tools like Microsoft Powerpoint can be used to create simple prototypes.

Being simple often enables real-time iteration. For example, during a research session, we can quickly redo part of a design based on a user’s comments in real time.

Low fidelity prototypes avoid being confused for a real service by users and stakeholders. This helps to keep the focus on higher level things we are trying to learn rather than the minor details.

High fidelity prototypes

This type of prototype is more realistic and closer to what an actual solution will look and feel like to users.

High fidelity prototypes are more detailed, they help us add extra functionality, whilst still not being fully functioning software.

That might be things like making buttons clickable, adding in logic so that different user responses lead to different paths through the prototype, or enabling users to populate text fields during their research session, so we can learn what they’d input, and how.

This helps us to better understand how people will use and feel about the services we are designing.

High fidelity prototypes for digital services are often written in code.

Reusable prototypes written in code can be quicker to write than graphics are to create. After a while there is no point creating a picture of the thing if you can build it with code in less time.

This is especially true if the team want to make regular changes in response to research.

What have we done so far?

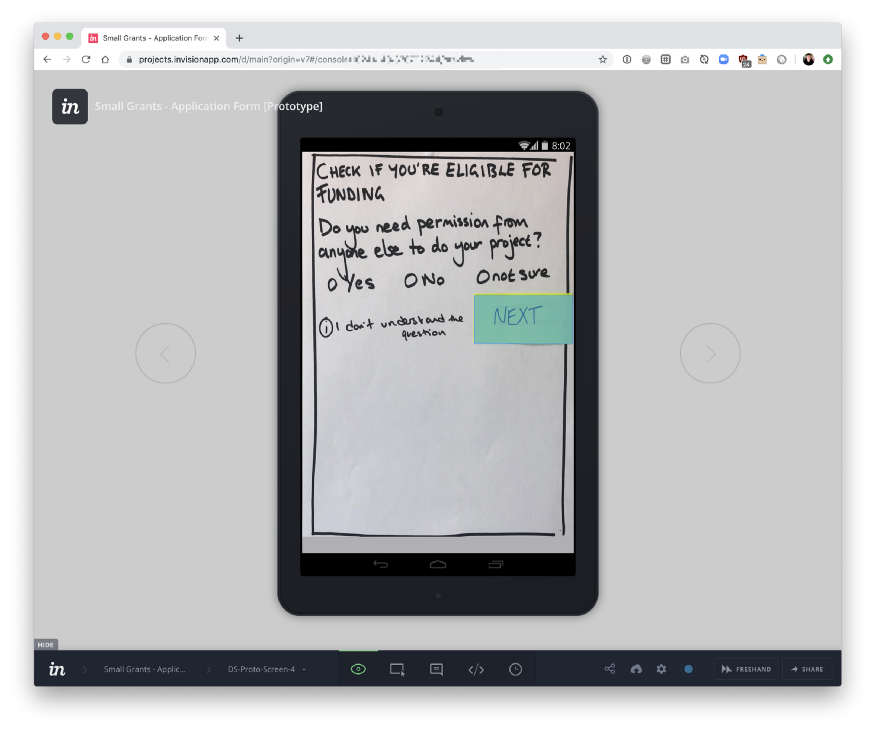

So far we are creating low-fidelity prototypes using good old-fashioned pen and paper as well as digital mockups.

Pen and Paper

We started on paper, in the same room as part of a group workshop known as a ‘design sprint’.

This was deliberate. Communication is in real time, it’s fast, it’s fun and at the start, the free flow of ideas and debate is best when done in person.

We analysed the existing live application form as a team. We invited members of our policy team to provide guidance and expertise.

Inspired by Ben Terrett’s GOV.UK Sketching templates, I created some sketch sheets for our team.

We used those to create a paper prototype of a redesigned application form, from the start to when a user clicks submit. Drawing out the content and flow of the questions onto the sketch sheets.

We took photographs of the sheets and then used a tool called Invision to make a ‘clickable’ prototype.

Digital ‘Mockups’

Pen and paper works well when you are in the same room but we are a distributed team.

The other drawback to prototyping on paper is that it eventually it does take longer. A mistake means redrawing a whole page or using fiddly bits of paper and glue which is fun but time consuming.

Once sketches are finished it then takes time to ‘stitch’ them together in Invision so we decided to try Balsamiq Cloud as our low fidelity prototyping tool to enable faster remote collaboration.

Balsamiq has a hand-drawn look that reminds us to stay lean and leave the little details for later.

The individual screen designs I call ‘digital mockups’. Some people refer to them as ‘wireframes’ but I try not to because ‘wireframe’ is a long standing industry term which can mean different things to people.

Where are we now (Sept 2019)

For two sprints we have used Balsamiq to turn digital mockups into prototypes that we have shown to our users. We have analysed the research and then iterated our prototype based on that.

We have kept copies of each version to refer to because an audit trail of those changes will be useful. Perhaps in conversation with stakeholders as evidence of what worked and what didn’t.

We are working fast to get to a version we feel confident about. At that point we will discuss investing time in either; making it a higher fidelity prototype or even a going straight to building a ‘beta’ service.

It is working well so far. All our team have sketched ideas and contributed to the prototype.

We have learned a lot and have been able to validate some of our ideas, and discard others. We can feel and show tangible progress every sprint, and we’re building confidence as a team that we almost have something that will do the job.

I am very pleased other members of the team (not just myself as official designer) have used Balsamiq to update prototypes.

They have learnt new skills and there is not such a dependancy on the person with ‘designer’ in their job title. After all, design and user research is a team sport!

What next?

In this third Alpha sprint we will conduct another round of research with users next week and analysis to follow up, and then we’ll discuss as a team whether we still have things we need to test and learn with this part of the journey, and whether our next steps should be a brand new prototype for the next part of the journey, or a higher fidelity or beta-ready version of this part.